The COVID-19 pandemic caused unparalleled social turmoil, altered the nature of human interactions, radically changed the workplace and left behind an enduring state of background anxiety. This has resulted in new pressures and unprecedented challenges for enterprises and individuals alike as they struggle to adjust to a new normal marked by continual transformation, independent and remote work environments, new technology, less personal interaction, greater demands accompanied by fewer resources, and heightened uncertainty and stress.1, 2

Prolonged stress can take a significant toll on mental health and result in burnout. In the simplest sense, burnout refers to mental or physical energy depletion or exhaustion resulting from chronic workplace stress and an inability to cope or manage.3 Burnout generally occurs when work demands exceed an individual’s ability to cope and the individual perceives a lack of autonomy, control or support. It is perhaps the most significant mental health issue plaguing the workplace today, and it is recognized in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases.4 It is often characterized by cynicism or negativism, a noticeable loss of energy, a lack of ambition or motivation, and feelings of helplessness or ineffectiveness regarding work.5, 6, 7 Burnout can have a range of health consequences, including anxiety, fatigue, headaches, gastrointestinal issues, immune system compromise, inflammation and insomnia.8, 9 It may also lead to more serious long-term health conditions such as depression, high blood pressure, heart disease and an increased proclivity for substance abuse.10, 11 In the workplace, burnout may have an adverse effect on morale and may diminish employees’ focus, motivation and productivity,12, 13 leading to additional organizational risk and compliance issues. Individuals suffering from burnout are more likely to circumvent controls, ignore policies or procedures, make errors, overlook details or take shortcuts.14

Burnout can manifest in any profession, regardless of workplace role, assigned tasks or level of responsibility, but auditors are particularly vulnerable, given the unique demands and challenges of the job. For many auditors, client and task demands, extended work hours, heavy workloads and unforgiving deadlines can make it difficult to achieve any kind of work-life balance.15, 16, 17 Internal and IT auditors are not always subject to the same built-in busy seasons as external auditors, but the continuous nature of the job and the always-on workplace culture can exacerbate stress and increase the risk of burnout. Burnout can negatively impact audit quality by making auditors more susceptible to cognitive bias and poor judgment and more inclined to conduct cursory reviews, overlook errors or use inadvisable shortcuts.18 Audit deficiencies may arise from an auditor’s inability to manage energy.

Auditors often relinquish control over their personal energy because they do not understand how energy works, and this lack of understanding makes them incapable of managing their own energy.

Most individuals respond to workplace pressures by putting in more hours, which eventually takes an even greater toll, since time is a finite resource.19 Therefore, it is not surprising that burnout is often attributed to a heavy workload and not enough time. Moreover, given the nature of auditors’ work, they often have a time-centric mindset, so the issue is framed as a time deficit problem, which suggests that the solution is to put in more time. But burnout is primarily an energy problem, not simply a time problem.20, 21 And unlike time, an individual’s personal energy is renewable.22 Auditors need to change their mindsets and focus on managing energy rather than time to avoid burnout.23

Understanding the Problem

Unfortunately, auditors often relinquish control over their personal energy because they do not understand how energy works, and this lack of understanding makes them incapable of managing their own energy. The Sustainable Model of Human Energy offers a useful framework to help auditors manage personal energy and reduce the risk of burnout (figure 1).24

Source: Quinn, R. W.; G. M. Spreitzer; C. F. Lam; “Building a Sustainable Model of Human Energy in Organizations: Exploring the Critical Role of Resources,” Academy of Management Annals, vol. 6, iss. 1, 2012, p. 337–396. Used with permission of Academy of Management (USA). Permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

The central elements of the model are job demands and resources. Job demands consist of anything an individual decides to do, whether that activity is something the individual wants to do or is asked to do. It is worth noting that job demands include both work-related tasks and nonwork-related tasks. Auditors increase their job demands when they choose to fulfill work obligations (e.g., perform assigned tasks, prepare deliverables, review others’ work, attend meetings, communicate with coworkers, mentor others). Auditors also increase their job demands when they choose to take care of themselves (e.g., prepare and eat meals, exercise, meditate, get adequate sleep, learn something new, pursue a hobby), fulfill family responsibilities (e.g., take care of children or older family members, perform household chores) or support their communities (e.g., attend events, volunteer, donate talent or money).

Meeting job demands requires the use of resources, which include anything an individual can access or control that can be used to turn plans into action. An auditor’s resources may include tangible things such as money, space, technology, equipment, raw materials or other individuals willing to lend a hand. However, resources also include intangible items such as energy, time, relationships, ideas, knowledge, skills and abilities. The sum of all available resources is referred to as total possible resources, and the resources consist of two basic types: resources in use, which are currently being used to fulfill job demands, and remaining possible resources, which are not being used at present but may be used in the future.

When auditors choose to invest resources to fulfill a job demand, they decrease their remaining possible resources and increase their resources in use. The difference between job demands and resources in use is the demand-resource discrepancy. When job demands exceed resources in use, an individual has a positive demand-resource discrepancy, which increases tense activation (feeling stressed). However, when resources in use exceed job demands, there is a negative demand-resource discrepancy, which increases energetic activation (feeling invigorated).

Because the relationship between job demands and resources determines whether someone feels stressed or invigorated, auditors can manage their energy level by carefully choosing which job demands to take on or ignore and which resources to access and use or save for later. Moreover, they can engage in resource seeking, choosing which of their remaining possible resources to convert into resources in use. This process often helps people realize they may not have the necessary resources. In this case, auditors may choose to create new resources to increase their remaining possible resources and, in turn, expand their total possible resources.

The creation of new resources depends on the breadth of thought/action repertoire, or the ease with which individuals can generate a range of options for themselves. Auditors with a broad repertoire are able to see more possibilities than those with a narrow repertoire, and a greater number of possibilities means more potential resources to choose from when attempting to solve a problem. Therefore, auditors with a broad repertoire of options at their disposal are more creative than those with a narrow repertoire. Creative thinking enables an individual to generate additional resources, which, in turn, increases the likelihood that resources in use will exceed job demands, leading to a feeling of invigoration. Feeling invigorated makes it easier to be open-minded, and feeling stressed makes it harder, so the breadth of options depends on how the individual is feeling. People find it easier to create new resources when they are invigorated rather than stressed.

Feeling invigorated also increases an individual’s intrinsic motivation, or the desire to do whatever results in positive feelings. Tasks that feel good may include overcoming challenges or performing familiar rituals. Greater intrinsic motivation can impact energy in three ways:

- Intrinsic motivation may increase job demands as individuals choose to take on difficult but achievable tasks that challenge them to stretch and grow their competencies.

- Intrinsic motivation may inspire individuals to take on enjoyable job demands that they find easy to fulfill, thereby reducing resources in use and preserving remaining possible resources.

- Intrinsic motivation may inspire individuals to practice difficult tasks until they become easier to perform. Over time (represented as delay in the model), practice leads to greater efficiency, thereby reducing resources in use and preserving remaining possible resources.

Intrinsic motivation may increase job demands as individuals choose to take on difficult but achievable tasks that challenge them to stretch and grow their competencies.

Hypothetical Auditing Scenarios

The model of human energy is relevant to auditors at all levels of responsibility. Although they may face different job demands and have different resources available to them, all auditors experience energetic activation (vigor) and tense activation (stress) and the associated consequences. Consciously managing these experiences allows auditors to mitigate the risk of burnout. Examples of what IT auditors at different levels of responsibility may encounter include:

- When audit staff tasked with testing IT general controls encounter situations they have not seen before, they may experience stress. This stress triggers the auditors to seek new resources, such as by searching the enterprise’s proprietary audit methodology for relevant information or asking colleagues for advice. As the auditors acquire the knowledge and ability needed to complete the assigned task, their stress decreases.

- When senior auditors review the work of audit staff, they possess the relevant knowledge and experience (i.e., the necessary resources) to spot errors, so they may feel invigorated. This feeling may make them perceive the task as enjoyable, so their motivation to hunt for errors may increase, making it easier for them to complete the task efficiently in the future.

- When audit managers are responsible for multiple tasks and have insufficient time to handle them all on their own, they may experience stress. Stressed individuals tend to be less open-minded and may not recognize the option of creating resources by teaching senior auditors how to perform the tasks and delegating responsibility to them. Audit managers may think the only option is to sacrifice their personal time and complete the tasks themselves. Accepting too much responsibility only exacerbates the problem, potentially leading to burnout.

- When senior managers at an audit or advisory firm feel invigorated and, thus, motivated to practice their business development skills (e.g., acquiring engagements), they initially invest a significant amount of time and effort. Over time, as these senior managers become more efficient at the business development task and can accomplish it using fewer resources, they will feel less stressed and more invigorated when approaching the business development task in the future.

- When audit partners who enjoy social interaction represent their organization at networking events such as conferences, they may feel invigorated, which may increase their motivation to engage in additional social activities (e.g., dinner with potential clients). However, additional socializing can deplete personal time needed for people to take care of themselves, which may result in less energy or more stress.

Strategies to help auditors manage their energy levels focus on increasing resources, decreasing job demands, making calculated choices about practice and monitoring activation.

Strategies to Manage Energy

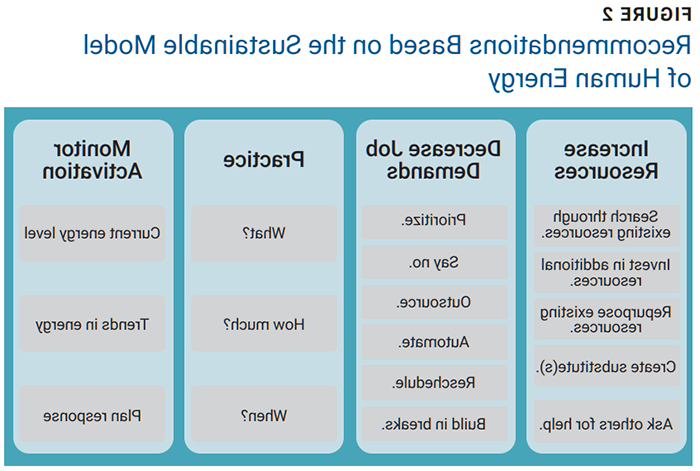

Strategies to help auditors manage their energy levels focus on increasing resources, decreasing job demands, making calculated choices about practice and monitoring activation (figure 2).

Increasing resources increases the likelihood of experiencing energetic activation (feeling invigorated) and decreases the likelihood of experiencing tense activation (feeling stressed). Organizations can help auditors increase resources by responding to specific requests for resources and offering resources such as job aids, mentors and training. Auditors can increase their resources in use by carefully searching remaining possible resources to identify those needed to meet current job demands. Auditors may also invest remaining possible resources (e.g., money) to obtain additional resources (e.g., software) to meet current job demands. Alternatively, they may use resources obtained for one purpose to fulfill a different purpose (e.g., use a bedroom as a home office), create substitute resources when desired resources are unavailable (e.g., use technology to automate repetitive tasks when staff are unavailable) and ask others to assist by providing labor, advice or other resources. These behaviors not only make individuals feel more energized, but also increase their ability to create resources and use existing resources more efficiently. Moreover, such behaviors likely decrease the need to search for additional resources in the future. However, it is worth noting that these behaviors may also increase the likelihood of taking on too many job demands in the future.

The effect of increasing resources is essentially the same as the effect of decreasing job demands. Auditors can decrease job demands by choosing to prioritize tasks with earlier deadlines first and scheduling less urgent tasks for completion later. Auditors can also decline to take on additional tasks when they lack the necessary resources to fulfill such tasks without sacrificing their ability to meet existing job demands. In addition, auditors can outsource personal chores (e.g., use Instacart for grocery shopping) or delegate work tasks (e.g., data extraction) that others are capable of performing, utilize automated procedures to carry out repetitive job demands, and negotiate or reschedule deadlines to reduce demands within a particular time frame. Another simple tactic is to build breaks into schedules or to take microbreaks (i.e., several minutes) throughout the day to allow time to rest and recover between fulfilling various job demands.

Practice may lead to future benefits. For example, effective implementation or use of analytics tools such as Python, UiPath, Alteryx and Tableau requires practice. Auditors should carefully consider what and when they should practice by answering the following questions:

- What provides enough value to justify spending time and effort on practice?

- How much practice (i.e., frequency and time) is needed to obtain desired benefits?

- Given competing job demands, when can practice be carried out without creating too many additional demands?

- Is it necessary to increase resources or decrease other job demands to make time for practice?

- Does the organization support practice by approving requests for additional resources such as access to experts, hands-on training and time to practice?

By carefully managing resources and job demands, auditors can ensure that their remaining possible resources are not depleted. This is a key concern, as the model suggests that undue stress may negatively impact a person’s health if the level of remaining possible resources gets too low. Therefore, auditors should monitor and forecast their resource levels and the job demands that consume those resources. The knowledge obtained from this exercise may inform decisions about when and how to increase resources, decrease job demands or both.

Auditors should also perform a cost-benefit analysis when making decisions about resources and job demands. To effectively manage energy, individuals need to assess whether the benefits obtained from job demands exceed the costs of resources in use. In the short run, when an auditor makes the right choices, the reward is energetic activation (vigor). When an auditor makes the wrong choices, the penalty is tense activation (stress). Auditors need to pay close attention to how they are feeling (stressed or invigorated), as these feelings indicate how well they are managing their personal energy. Thus, benefits may accrue to auditors who monitor their personal levels of energetic activation and tense activation (both current levels and trends over time) and use this information to balance resources and job demands and better manage their personal energy while still achieving goals.

There are other practical implications of the model. For example, it predicts that tense activation and energetic activation may grow over time, and both can exist at the same time. This means that individuals may be simultaneously more stressed and more invigorated than they were yesterday, but the earlier feeling will likely be stronger, as it has had more time to grow. This suggests that it is a good idea to start the day well rested and free of tense activation. Auditors anticipating a demanding day tomorrow should practice self-care (e.g., adequate rest, exercise, family activities) today.

Auditors must continually monitor resource consumption and remaining possible resources and adjust behavior as needed.

Even if auditors can effectively manage energy levels to attain greater energetic activation than tense activation, they should remember that the relationship between job demands and resources is not static, so they need to actively monitor energy management. If an individual can find or create resources faster than job demands consume them, the feeling of energetic activation may exceed the feeling of tense activation, indicating effective energy management. But this relationship might change. The ability to find or create resources may eventually hit a ceiling, whether due to individual actions or forces outside an individual’s control, even as the need for resources continues to grow. Alternatively, auditors may encounter a tipping point when job demands start to consume resources more quickly than new resources can be found or created (e.g., when assigned a new role or responsibilities). The danger lies in auditors being blind to such changes and assuming that resource consumption will continue at the same rate or that remaining possible resources will always be available. To mitigate this danger, auditors must continually monitor resource consumption and remaining possible resources and adjust behavior as needed.

Conclusion

Monitoring and managing personal energy to avoid burnout is not an easy task, especially for auditors in high-demand environments such as those associated with busy seasons or an always-on culture. The Sustainable Model of Human Energy offers an alternative to a time-focused mindset that auditors can use to understand prolonged workplace stress and burnout and bolster their resilience. It also offers a framework for developing strategies that can be consciously employed to mitigate chronic energy depletion based on the relationship between job demands and available resources. But it is important to note that not everyone has the same job demands or resources, and strategies designed to manage energy will not have the same impact on everyone. Auditors should cultivate an energy management mindset, carefully consider how it applies to their unique circumstances and then experiment to determine what works best for them.

Endnotes

1 Alvero, K. M.; “Mindset Matters: A Permanent Shift to the New Normal in IT Audit,” ISACA® Journal, vol. 2, 2022, http://9fsw.1acart.com/archives

2 Rudes, H.; “Combat Employee Burnout and Prioritize Mental Health at Your Firm,” Accounting Today, 1 July 2022, http://www.accountingtoday.com/opinion/combat-employee-burnout-and-prioritize-mental-health-at-your-firm

3 Psychology Today, “Burnout,” http://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/burnout

4 World Health Organization (WHO), “QD85 Burnout,” International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision, February 2022, http://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281

5 Op cit Psychology Today

6 Op cit WHO

7 Muldowny, S.; “Extinguishing Auditor Burnout,” Acuity Magazine, 9 October 2021, http://www.acuitymag.com/business/extinguishing-auditor-burnout

8 Op cit Psychology Today

9 Mayo Clinic, “Job Burnout: How to Spot It and Take Action,” http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/burnout/art-20046642

10 Op cit Psychology Today

11 Op cit Mayo Clinic

12 Ibid.

13 Op cit Rudes

14 Hurley, P. J.; “Ego Depletion and Auditors’ JDM Quality,” Accounting, Organizations and Society: vol. 77, 2019, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2019.03.001

15 Hitchcock, W. R.; “Auditor Strong: A C.P.A. Plan for Resilience,” University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 1 August 2021, http://repository.upenn.edu/mapp_capstone/223

16 Op cit Muldowny

17 Deloitte, “Workplace Burnout Survey,” http://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/burnout-survey.html

18 Hurley, P. J.; “Ego Depletion: Applications and Implications for Auditing Research,” Journal of Accounting Literature, vol. 35, 2015, p. 47–76, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.acclit.2015.10.001

19 Schwartz, T.; C. McCarthy; “Manage Your Energy, Not Your Time,” Harvard Business Review, vol. 85, iss. 10, 2007, p. 63–73, http://hbr.org/2007/10/manage-your-energy-not-your-time

20 Op cit Psychology Today

21 Op cit WHO

22 Op cit Schwartz and McCarthy

23 Ibid.

24 Quinn, R. W.; G. M. Spreitzer; C. F. Lam; “Building a Sustainable Model of Human Energy in Organizations: Exploring the Critical Role of Resources,” Academy of Management Annals, vol. 6, iss. 1, 2012, p. 337–396, http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-18051-007

ELENA KLEVSKY | PH.D., CPA

Is an assistant professor of accounting at the University of Tampa (Florida, USA) and a member of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) and the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Previously, she was a senior associate working in the audit area at PricewaterhouseCoopers. Her articles have appeared in Fraud Magazine and Strategic Finance. She can be reached at eklevsky@ut.edu.

MELISSA WALTERS | PH.D.

Is an associate professor of accounting at the University of Tampa (Florida, USA) and a member of ISACA® and The Institute of Internal Auditors (The IIA). She has worked in the areas of systems advisory, implementation and support and teaches information systems and IT advisory and assurance topics. Her articles have appeared in the ISACA® Journal and Management Accounting Quarterly. She can be reached at mwalters@ut.edu.